I first encountered Cornell format note taking in a college education class for teaching reading. I used it with my advanced French classes somewhat, but it became one of the cornerstone activities of my social studies classes beginning around 2006.

Cornell notes is a process that encourages developing reading skills, especially for informational text. It provides a study guide for later, although in truth few of my students used that. In my own experience, this method stimulates long-term memory. I believe this is because to complete the task one returns to the information at different levels of abstraction from text to outline to questions and finally to abstract of the whole. The repetition and organized structure of the information promotes that encoding into memory. In addition, it makes a good class activity: upon completion, students can ask each other their questions in a round-robin or pairs format.

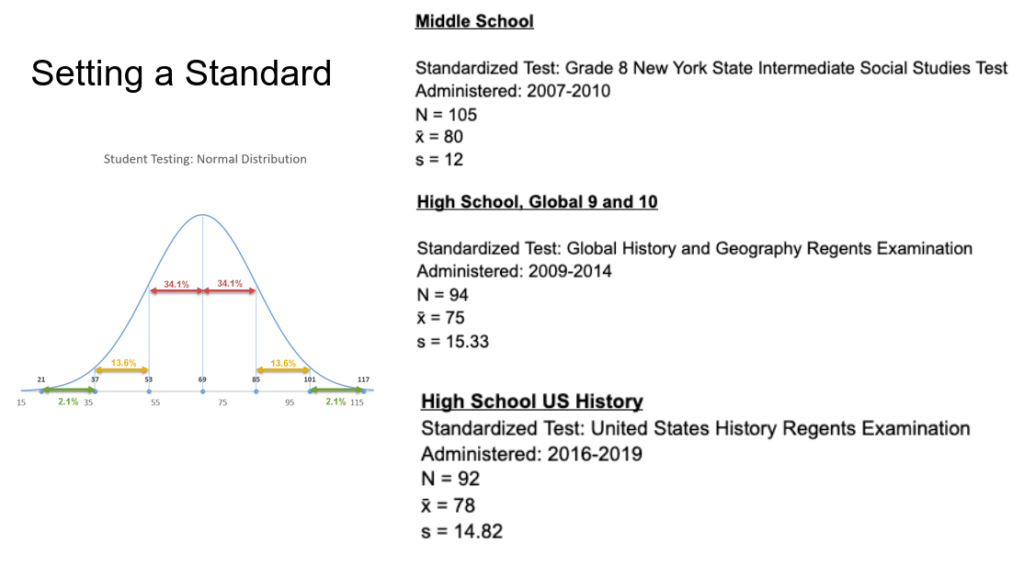

The two informal studies below I conducted in 2013 and 2014 to examine the effects of this method on my students’ progress in social studies. Cornell notes became one of two options students had for processing their reading assignments for each unit. The other was summarizing, an equally effective skill. Consistently, about half my students preferred this method.

Originally posted May 2013 and February, 2014.

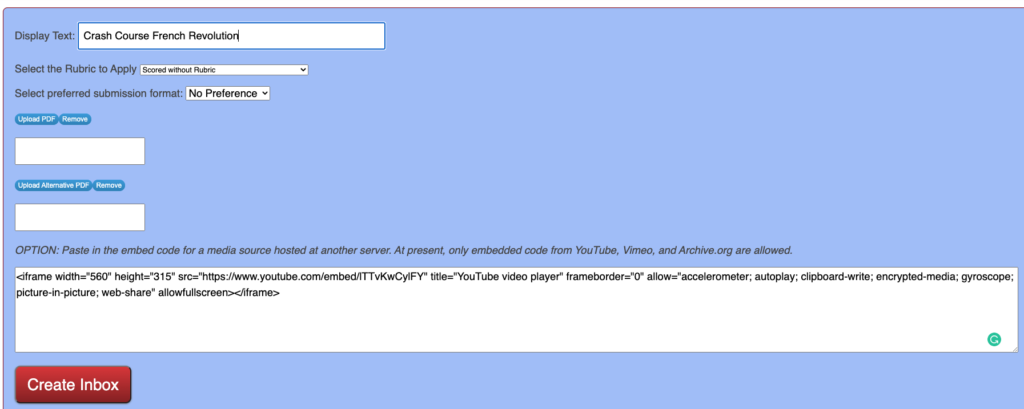

Innovation has an app now for students to compose Cornell Notes online! And the AI grading assistant can help you score the notes!

May, 2013

A Study of a Reading-Note Taking Task as Interim Examination Improvement Strategy

“Interim examination” refers to a regularly occurring examination measuring all course content since the start of the course. They are given at regular intervals as a progress monitoring method. They should be highly reliable indicators of achievement in the course (such as being highly predictive of performance on a standardized test) and teachers ought to be able to use the data to make decisions about instruction. A point worth emphasizing about the interim examination is that it is a test that spirals: each successive examination tests the content knowledge of the preceding tests and what had been taught since.

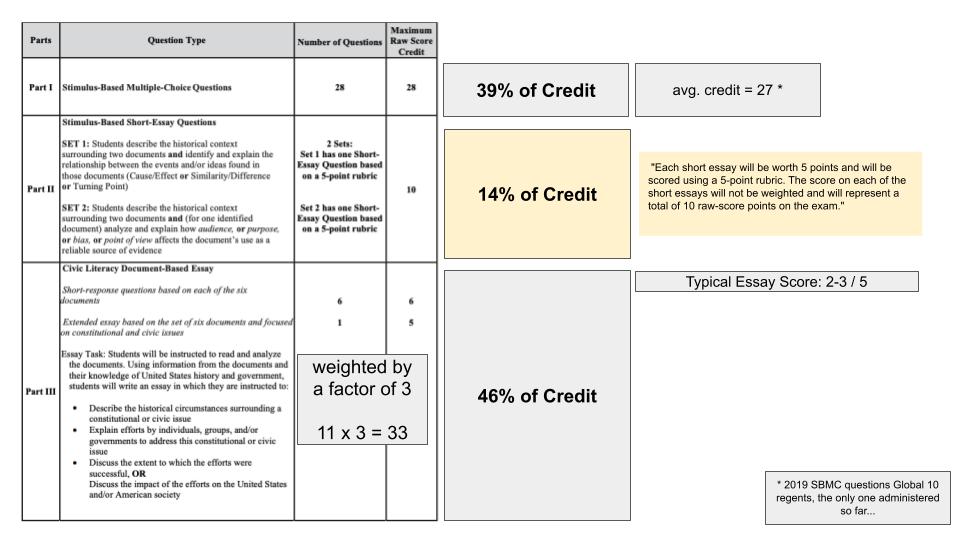

Forty-five students in grade seven through nine social studies at Schroon Lake Central School took the second interim examination in January 2013. Results for some classes were disappointing. An instructional plan was devised to improve student performance by the April interim examination. The most important aspect of this plan was a reading & note taking task. Secondarily, there was some increased exposure to domain-specific vocabulary.

The effort appears to have been successful. 17% more students passed the third interim examination from the second. The mean score went up 6%. The probability that the improvement was not due to random chance or other variables is 83%.

The Note Taking Task

The note taking task that was intended to boost student performance had two components: notes from textbook and notes from lecture. Notes had to be taken in Cornell Note Taking format. Cornell format training has been regularly included in the courses, including training at the start of quarter 3 on using Bloom’s Taxonomy to create higher level questions on the notes. The note taking task is graded as a “high order task” (high order tasks account for 65% of a student’s GPA in the course). Cornell Note Taking is a note taking technique well supported in research1. Students have two full class periods to begin the text note taking and then additional working periods when they may opt to do that. They have twelve days to complete the task as this is the time a topic usually runs.

Notes from textbook could come from any of three sources, designated as “below”, “at”, or “above” grade level. Grade level difficulty level was determined using Lexile and gauged by the Common Core State Standards grade level reading expectations. Students self-select for difficulty level in consultation with me. The amount of reading ranged from 8-12 pages.

Students doing the standard curriculum normally have 1-2 persuasive composition quizzes and 2 expository composition quizzes in each topic. The lecture included some information and media presentations intended as background or to reinforce key ideas as well as the direct answer to the composition quizzes. Notes required from lecture were limited to those aspects of the teacher presentation series that answered specific quiz questions. A modified lecture notes task is optional for students who are not sufficiently able to take notes. They get a copy of the presentation materials and add notes and create questions as for Cornell notes. The maximum score on this is 76 owing to the reduced workload.

Student Performance on the Note Taking Tasks

There were two notes tasks in the third quarter. The average score on the notes task was 70, the median 85. Around a quarter failed the notes task each time. Around half of the people who failed the average of the notes tasks failed interim three. The average score on the notes task was bore a moderately high correlation to year-to-date GPA in the course (0.70).

Twenty-seven students responded to a survey in which they were asked how well they like the addition of reading-note taking to their classroom tasks. 75% responded favorably. Prior to this change, assigned reading tasks were few. Save for grade nine, who had one short reading task per week as homework, students could get the information they needed to pass the quizzes elsewhere other than text – including studying the quizzes of students who took the quiz before them. The amount of regular reading in class had become far too limited. My focus on performance on content knowledge quizzes and on writing took me too far afield of reading for a while.

February, 2014

TOPICAL READING ASSIGNMENT USING CORNELL NOTE TAKING

For each topic of study over the year from February to February 2013-2014, students in social studies grades seven through nine at a small, rural school (N=~50) were assigned to use Cornell note taking for their assigned textbook

chapter readings. The practice was initiated as a response to weak performance of some groups on the 2013 midterm examination.

Students are assigned ten pages of traditional textbook reading associated with the current topic of study. They may choose from three levels of text: a fourth-grade text, a grade-level text, and an advanced level text set at two grade levels higher. Providing reading material close to students’ independent reading levels gives them meaningful access to the information and support for continued reading growth (Allington, 2009). Students have two 45-minute class periods to work on the assignment and are expected to complete at least five pages per class period (this is more than double the time it takes the teacher to do the task). This assignment occurs before teacher lecture and is intended to support student learning by providing the basic groundwork information of the topic.

Students are trained in the Cornell note taking format (Paulk, 2014). Using a form provided by the teacher, students create an informal or formal outline of the most important top two layers of detail from the source text in their own words (Marzano, 2001). Next, students create questions to go with the information they recorded. Students are trained in a basic version of Bloom’s Taxonomy for the development of questions and are encouraged to devise questions and the analysis and evaluation levels in support of long-term memory of the information. Finally, students are to construct an abstract of each page of notes at the bottom, summarizing the main idea of the whole page in one or two sentences. Students are graded on the quality of their notes (Figure 2).The task is due at the end of the topic, usually around two calendar weeks later. Students have additional “working days” after the teacher lecture series, some of which they may dedicate to completing whatever was not yet done of the reading task.

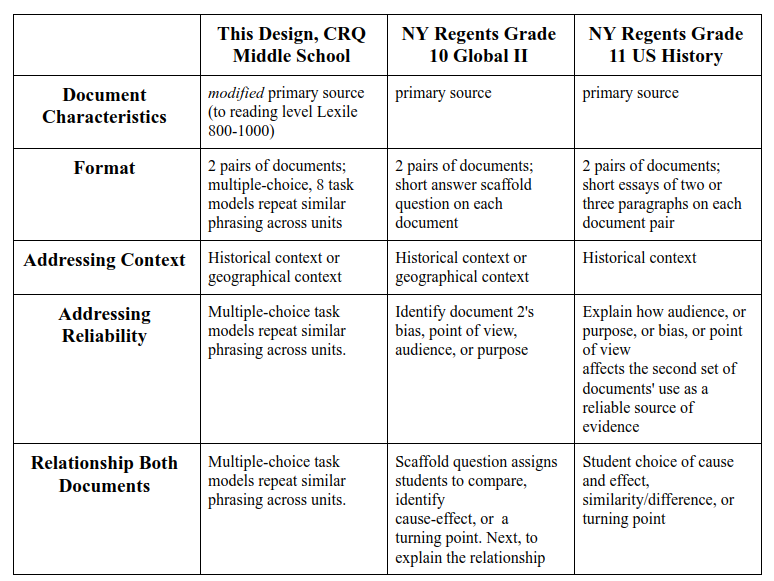

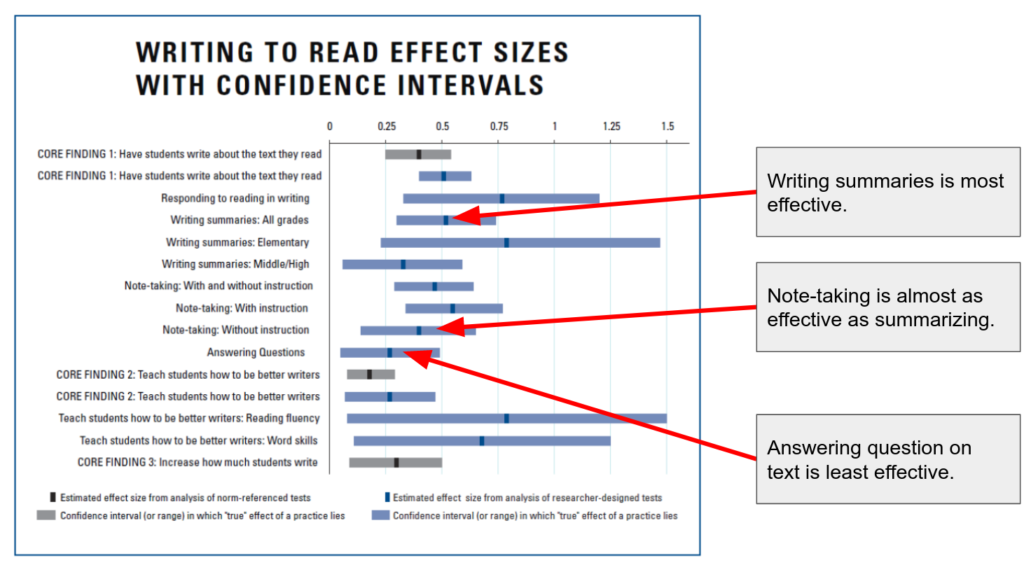

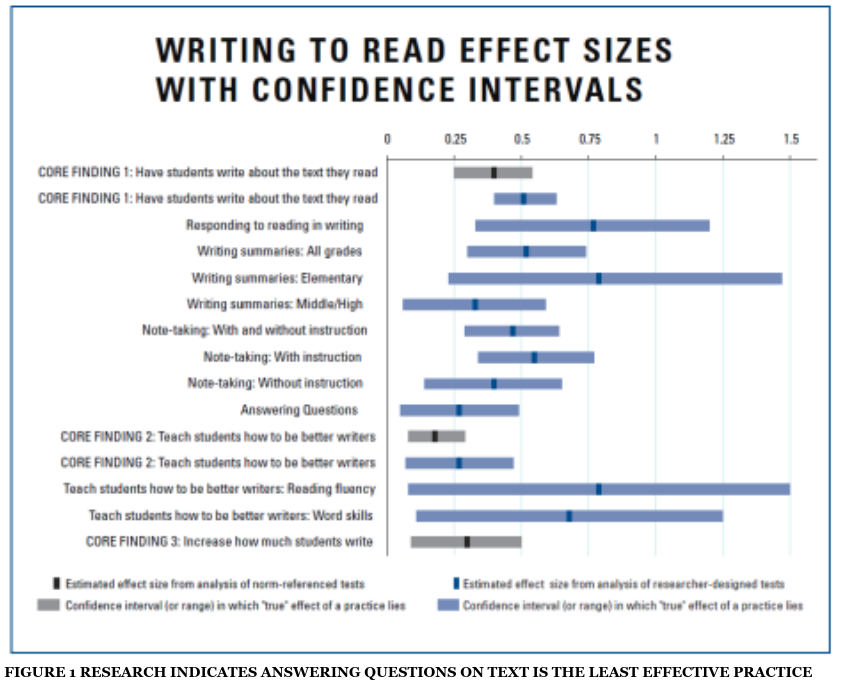

Students are assigned the Cornell note taking method because of the strong supporting research (Figure 1). Research indicates answering questions on text to be least effective for supporting reading comprehension (Graham, 2010). Cornell note taking supports higher level thinking such as application, synthesis, and analysis (Jacobs, 2008). Note taking is one of the “most powerful skills students can cultivate” by providing “students with tools for identifying and understanding the most important aspects of what they are learning.” (Marzano, 2001). It supports encoding the information for long term recall more effectively than guided notes and questionnaires (Jacobs, 2008). Note taking is known to be an effective strategy “if it entails attention focusing and processing in a way compatible with the demands of the criterion task.” (Armbruster, 1984) In effective note taking, research suggests, happens when “students failed to take notes in a manner that elicited sufficiently deep or thorough processing.” (Armbruster, 1984)

REASONS TO CONSIDER EXAMINING THIS TASK

Informal feedback from students shows the task is generally disliked. The two periods are not maintained strictly as silent working periods, though distraction is generally minimal. Weaker students are observed to be often off task. Examination of work accomplished throughout the period indicates some weaker students complete only a page during the whole time. The completion rate for this task only averages 80% in each topic September-January 2013-2014 grades seven through nine (N=54). Increasingly, this task is coming in late and poorly done with the mean score at only 72. The lack of sustained attention to task during the class periods allotted for this task likely decreases the effectiveness of the task, especially memory of the information (Armbruster, 1984).

WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES PERFORMANCE ON THE READING TASK MAKE?

Five students in the sample who had a passing average for the reading tasks assigned in the 2013-2014 school year to date failed an interim examination1.

Eighteen of fifty-four students in the sample (33%) have a failing (below 65) average for the reading tasks. This includes scores of zero assigned for incomplete tasks. Half of the students who have a failing average for the reading tasks failed an interim exam. Five (9%) failed both interim examinations and four (7%) failed one of two interim examinations.

Only nine of eighteen students with a failing average on the reading task were able to pass both interim exams.

“Interim examinations” are ten-week tests of knowledge of course content going back to the start of the school year.

“Interim examinations” are ten-week tests of knowledge of course content going back to the start of the school year.

The reading task score measures how well students extracted the “study-worthy” ideas from the source text and prepared this content for learning. In this sample it was a weak predictor of performance on both the topic final test (correlation is 0.419) and the interim examination (correlation is 0.334). This stands to reason, since the measurements are for different things. Final tests and interim examinations are measures of knowledge of content.

For the 16th topic of study in grade eight, the task was set up as a “test”. Students were given 30 minutes to complete 5 pages. Students who needed more time received it, though a timer was left obvious and the room remained silent. Students commented that they felt they got a lot done in the more disciplined atmosphere. I am now assured that the class has completed the requisite reading assignment to understand the upcoming lessons and that the task was carried out in the most meaningful way possible.