Dear fellow social studies teachers,

I would like to play the role of a crusader in this post, if you don’t mind. There’s something I would like you to consider about your teaching practice, or maybe reconsider as the case may be. I’d like you to abandon assigning your students comprehension questions on most kinds of texts you assign in your social studies class. Instead, I’d like you to consider assigning students to summarize instead.

When students do the search and copy instead of reading the text fully, they deny the author the chance to build with the reader an information schema of their own that lends itself to long-term recall.

Okay, so who do I think I am anyway to question a practice that’s at least a century old? Well, I cannot claim to be any super authority. I taught social studies for eighteen of my thirty-two years teaching. I worked in small, rural mountain schools and my roster averaged about one hundred students a year, which is likely smaller than that of my readers. I think these are good starters to convince you to at least hear me, but I have always felt that the argument from authority to be one of the most pernicious fallacies. So in honor of my thirty-two years, grant me the indulgence of reading further. As for accepting my suggestion, let the arguments sway you themselves.

When you assign your students to read a text selection and answer questions on it, you must know what the majority of them do. They skim the text to locate the answer, often they copy it wholesale, and then they’re done. Teachers who accept this kind of work are missing an important opportunity to foster greater reading comprehension skills and greater long-term recall. Writers, even writers of textbooks, build meaning in a schema of content to deliver to the reader, who constructs meaning related to their experience. Ideas are hierarchically arranged and organized to support a set of main ideas. When students do the search and copy instead of reading the text fully, they deny the author the chance to build with the reader an information schema of their own that lends itself to long-term recall. At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, questions on text are largely a useless exercise even when the questions are of high quality.

Once students leave sixth grade in my region, the formal lessons in reading stop. But a great number of sixth graders do not read at a sixth-grade level. They cannot advance their reading without texts at their level. And they have to actually read these. It is possible and desirable in middle and junior high school to promote the development of reading in youngsters by structuring what they do to process text. Teaching students to write competent summaries is one of the best ways to let them develop their reading skills. (This should be paired with offering texts at their independent reading level whenever possible).

What does the research say?

Summarizing and note-taking are two of the most useful academic skills students can have. (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2005)

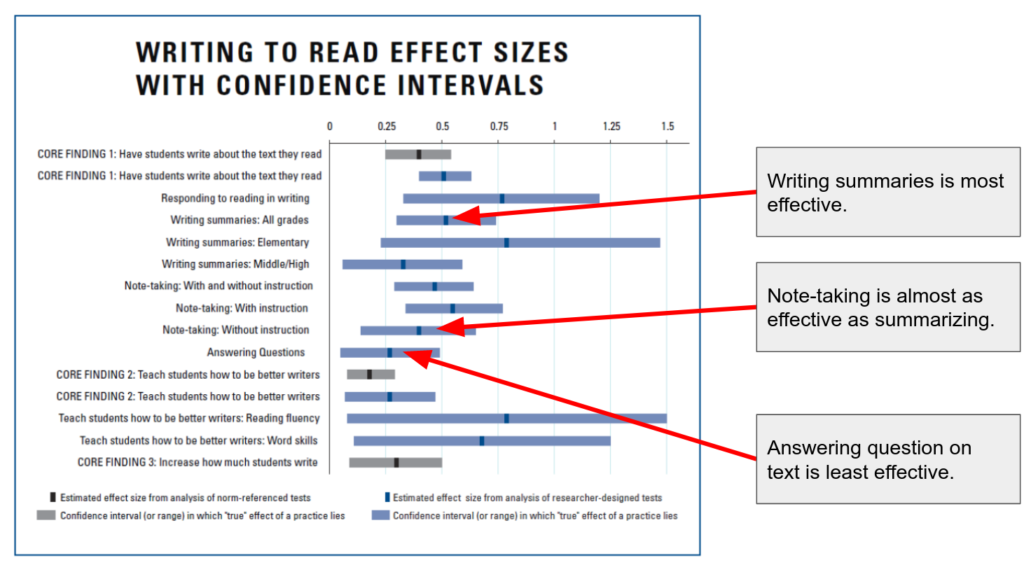

Summarizing is in the top two most powerful writing tasks that support the development of student reading. (Graham & Hebert, 2010)

Writing to Read

I was greatly influenced by a paper entitled Writing to Read: Evidence for how Writing can Improve Reading in 2010 published by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. A meta-analysis clearly demonstrates that composing summaries is superior to answering questions on text. The reader may argue that this research was conducted to address methods for using writing to enhance reading. But I would argue that (a) this is rightly a major goal of assigning most secondary students a textbook reading task and (b) the same cognitive processes that go into reading comprehension go into long-term recall of information. Students answering questions on text are less likely to be encoding from working memory into long-term memory than those composing summaries in their own words.

The Five and Three Summary Style

Around 2006 when I was making major investments in curriculum and methodology development, I sat down with a noted professor of literacy who happened to be working in our district, Trudy Walp. I explained my qualms about assigning students questions on text and I asked her, what is the very best thing I can have students do with text from a reading specialist’s perspective. She did not hesitate to say: have them retell what they read.

When I assigned my students summaries on their textbook articles early on, my top students wrote terribly long and detailed compositions that were not brief enough to be a summary. I needed to shorten my students’ summaries and to develop a rubric for evaluating the quality of a summary. The resulting task I used for some fifteen years: the Five and Three.

The assignment for the five and three is to summarize the assigned text (usually four pages in a typical high school textbook) in five sentences exactly, no more and no less. This is the “five”. The “three” is the personal reaction to the text. Students were assigned to connect this text to their own life somehow. What does it remind them of? What do they think about what they read? Why? These had to be exactly three sentences long. This was the second element that the reading specialist recommended to me. Students need to make the text meaningful to them in some personal way that makes new information integrate into their preexisting schema.

The five-and-three became the foundation of my students’ textbook reading work. They also had the option of composing Cornell notes for an assigned reading. I would invite the reader to return to the blog for a post dedicated to extolling the virtues of Cornell note-taking. The five-and-three faded in importance in certain classes where video lessons became an effective information delivery tool when reading instruction was no longer a priority.

The Mechanical Summary

The mechanical summary evolved in 2020 when I had a group of learners who struggled and who just would not produce summaries even given time to do so in class. I offered them the opportunity to write a summary by copying the first sentence of each paragraph word-for-word, then to connect and arrange these into complex sentences such that there were only five sentences. They had to compose the three-sentence personal reaction to the text just like normally done. For this, I offered a maximum score of 76 because, I argued, it had less value not being processed in their own words. I reason that not processing in their own words likely limited the ability of encoding to happen from working memory to long-term memory.

With the Assistance of AI

At this point you are likely wondering how you could possibly grade all these summaries. I will grant you, the workload takes some management, but I would argue that it is only slightly more time consuming than grading answers to a set of questions and the benefit to your students makes it all very worth it.

I’m an amateur programmer and I developed an AI grading assistant that is very good at scoring summaries. This app is available to subscribers to Innovation Assessments. Say, why not sign up for a free 60-day trial? The price is surely right if you decide to subscribe?

The AI grading assistant was accurate enough to save me tons of time scoring summaries. The summarizer app actually let me create models on which to train the AI that were highly accurate when compared to human-generated summaries… eerily so!

This blog post describes the AI grading assistant.

The ability to skillfully summarize is a lost art worth recovering for our students. It enhances the development of their reading ability and it promotes greater recall of the content we teach. It’s my hope my experience developing this system can make this suggestion seem do-able and worthwhile.

SOURCES

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2010). Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading. New York: Carnegie Corporation.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2005). Classroom Instruction that Works: Research-Based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.