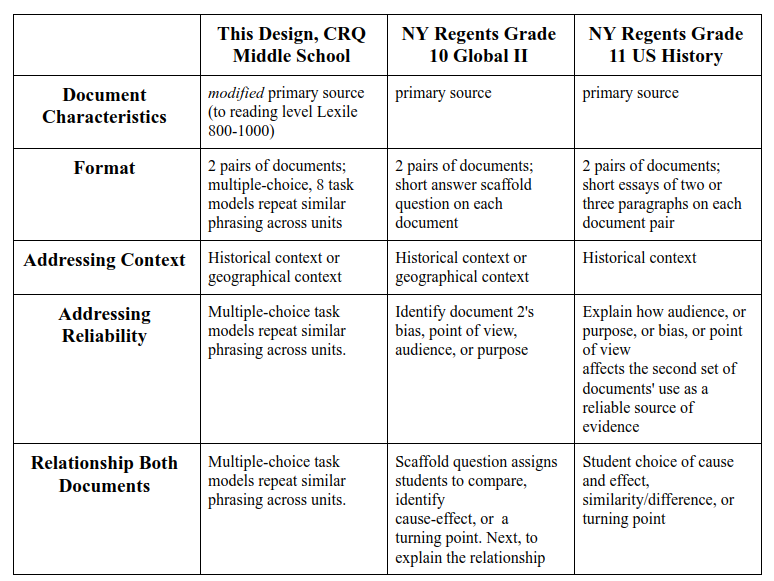

The purpose for introducing the constructed response question (CRQ) in middle school is to prepare students for this kind of assessment later in their education. Ideally, the task should lay the groundwork for the habits of mind that promote success and should accustom students in a practical way to the assessment itself, its common form and its vocabulary. Experience teaching this to eighth graders shows that one of the first major obstacles is to get students to move away from the reflex ingrained in elementary school: to respond to a text by stating what it says. The second major obstacle to teaching this is that students coming out of elementary school are wholly unfamiliar with the idea that some materials they may be given are quite possibly not reliable. In addition, they lack the vocabulary to manage the concepts of text reliability.

It is difficult for upper elementary students to address primary source material for a variety of reasons. First and foremost is the text complexity. Secondly, a limited ability to comprehend given their severely limited background knowledge (class lessons should remedy this). The middle school CRQ needs to be accessible to most students while still preserving the “primary source” characteristic of the task; the opportunity to see what people of the past had to say in the way they said it. It is often a further revelation to people at this age that the English language has not always existed or that it has existed in variant forms they would find incomprehensible. An appreciation of language change and variety plays an important role in addressing primary sources for this age not only for a deeper understanding but to appreciate reliability concerns of translation and excerpts and secondhand accounts. The documents for analysis in the middle school CRQ will be carefully devised in the following ways:

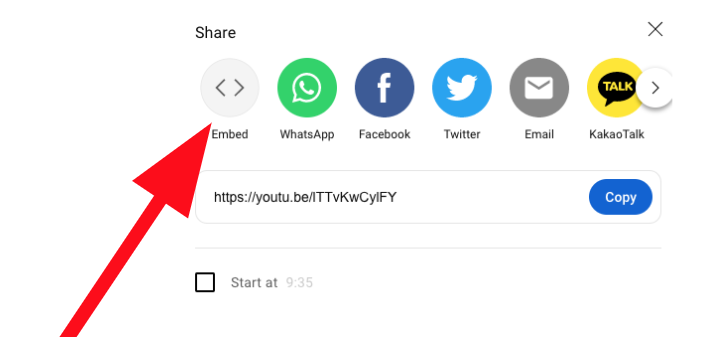

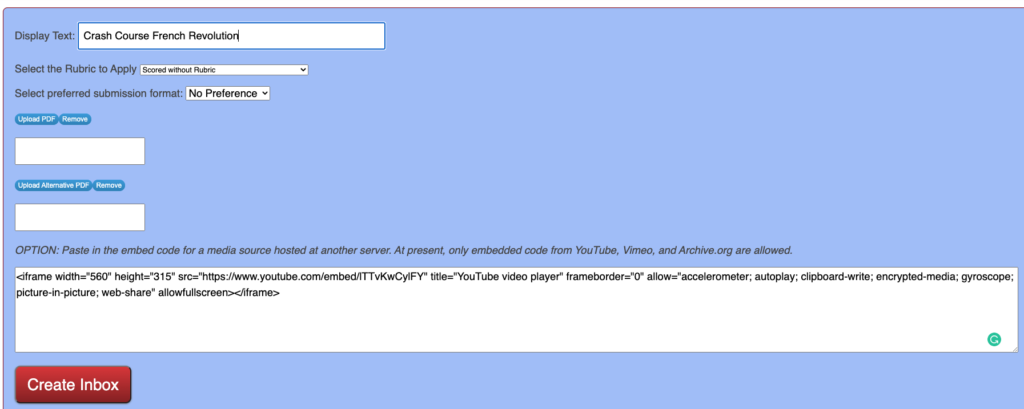

- An image of the source’s original format and language will be provided for purely observational purposes. This may be merely an incomplete image or fragment.

- A standard translation of the source will be provided despite that it is at a text complexity above the grade level band. This is also purely for observational purposes, though some students may make the attempt to analyze it.

- A translation of the source into a Lexile range of 800-1000 will be provided if necessary. This is the document on which students are to work.

- There will be a citation of the source in the simplified version of the citation format used by genealogists. Students should consider the source in their analysis.

One task will consist of two pairs of documents. Students will give the historical or geographical context of the first document in each pair. Students will assess the reliability of the second document in each pair. In addressing the reliability of the source, students will need more support, naturally, than their compatriots at the high school level. The second document in each 2 pair will ask the student to address reliability in multiple-choice format. This will habituate the student to the typical phrases used in addressing reliability. First, students will be prompted in multiple-choice format to identify the document’s bias, point of view, audience, or purpose. Secondly, students will be asked to identify the best use of the document for a historian or anthropologist. Thirdly, a multiple-choice format question will ask the student to conclude how the reliability factor affects this document’s use as a reliable source of evidence to prove something specific. This latter point is important to help students understand that sources may have different reliability depending on what the historian wishes to do with them.

The last part of the task calls upon the student to synthesize a relationship between documents 1 and 2. This will also be in multiple-choice format. Students will be prompted to use both documents in one of three possible ways: (a) state a similarity or a difference between the documents; (b) explain one change associated with a turning point in history that the documents reflect (the turning point will be identified for the student); (c) explain how some development or idea is the cause of some event, idea, or historical development reflected in both documents.

Gradually toward the end of grade eight, students will move toward short answer format CRQ’s as they will see in high school. Having seen the same wording each unit across grades six through the first part of eighth, the idea of context, reliability, and turning point should be well established. A multiple-choice version for students who are still developing the skill could be offered for a reduced maximum score.

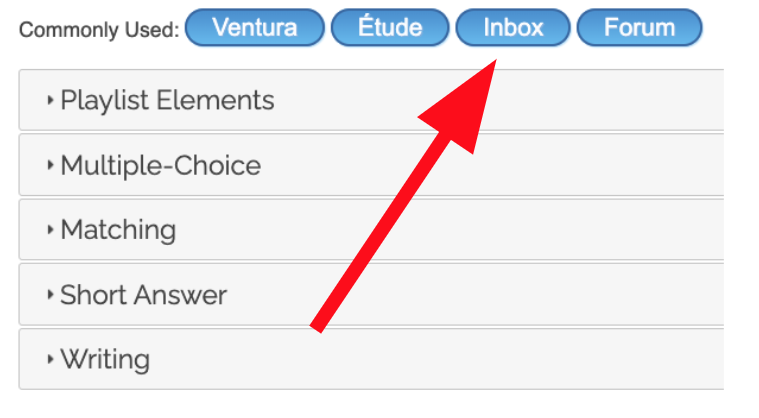

Task Models

Borrowing from the “task model” concept used in developing the New York State Global history and Geography Regents examination part one (stimulus-based multiple-choice), the following are the task models for the multiple-choice version of the middle school CRQ. It will be important to use similar language in constructing the questions for consistency.

- Which of the following [statements | titles] best represents the [historical | geographic] context of the [document | map]?

- Correct answer will be historical background information not present in the document

- One incorrect option will be of the type “This document is about…”

- Correct answer will be geographic background information that explains the origin of the map’s information

- One incorrect option will be of the type “This map is showing is about…”

- Which of the following statements best represents the geographic context of the map?

- Which of the following would be the best use of this document for a historian?

- Which statement best describes the [point of view, intended audience, purpose, bias] of the document?

- When point of view is asked, one incorrect option will be “first person’ or “third person”. This is to teach the student to distinguish between how that term is used in English and how it is used in social science.

- Which of the following factor(s) would [weaken | strengthen] the reliability of this source for the purpose of __.

- The reliability factors taught are: authorship, format, point of view (objective or biased), time and place, intended audience, purpose.

- These will often have more than one correct answer.

- The factors are listed, followed by a colon and a description. Example:

- Point of view: The author is very biased.

- These two sources are artifacts from a turning point in history. Which would be the best title for that turning point?

- Which statement best describes a [similarity | difference] between the two sources?

- These two sources are artifacts from historical events. Which statement describes a cause-effect relationship of the historical events the sources represent?

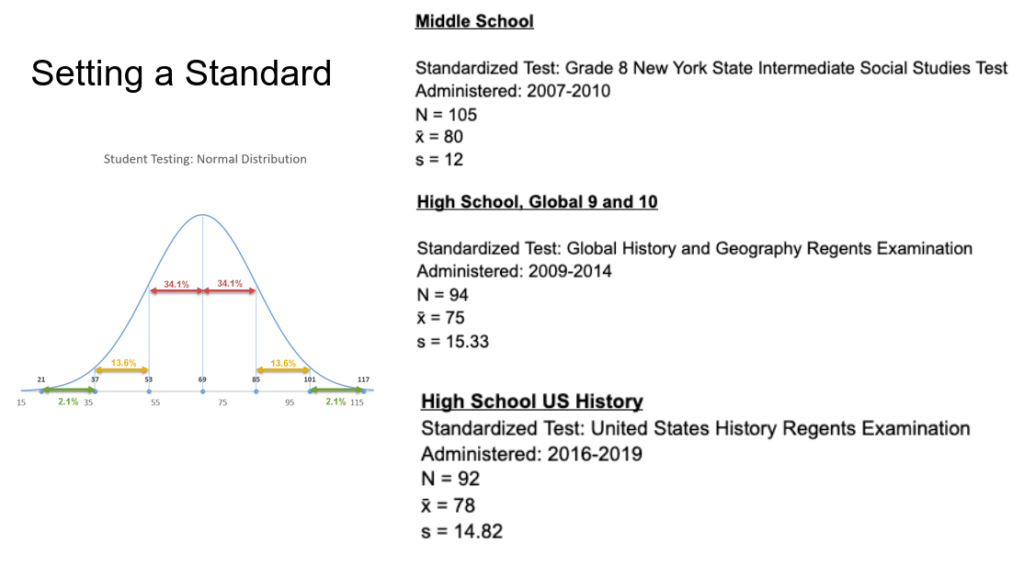

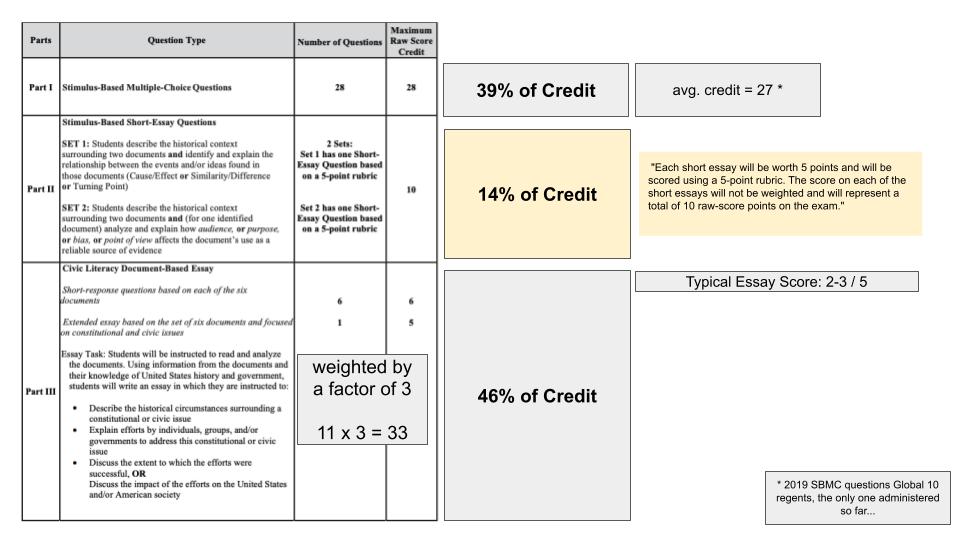

Assessment Task Comparison Across Three Assessments

The purpose of developing this task is to create a logical early training step for students in middle school working toward the assessment tasks they will see in high school.