In my grandparents’ day, we’re talking the 1930s, students who took world languages in high school were really aiming for a reading knowledge of the language. College-bound students of that era would be ready to read sources in their original language perhaps, and not so much ready for travel. In the hand-wringing self-criticism of the 1980s and 1990s, there came a growing concern that world language courses were not “communicative” enough. Students lamented that they took four years of such-and-such language and couldn’t actually speak it.

So in the spirit of reform, when I was being trained as a language teacher in the early 1980s, we were baptized in the holy water of communicative proficiency and realia.

I wish to demonstrate that teaching culture using the target language is an effective means of getting students to communicative proficiency.

But here, decades later, I have to seriously question this focus for students after the second year in a high school world language course. My reason is pretty simple: despite the great reform of those decades and the sincerest efforts to produce good communicators in the target language, world language high school alumni still rightly complain that they cannot really speak any of the language they learned. The criticism still stands.

We all seem to just accept this and the way it goes. World language teachers have lobbied for years, successfully, to promote our stock and trade. Among the benefits we can tout are an enhanced understanding of other peoples, possible career opportunities for those who develop proficiency, improved reading and writing competency in their own language, and so forth. What we cannot say is that our charges will retain the skills we taught them. Even my French four students came back years later to visit with their once-honed language skills dissipated completely. The fact is, one cannot develop linguistic proficiency in the traditional classroom.

The main reason to do this is that learning culture will stay with students longer and enhance their overall education more profoundly than learning a language they will most assuredly mostly forget.

I want to promote a way to teach world language in high school years three and four that makes learning another language highly satisfying while at the same time achieving whatever basic linguistic proficiency is possible in the traditional high school classroom.

Click here to shop for French civilization units in my store.

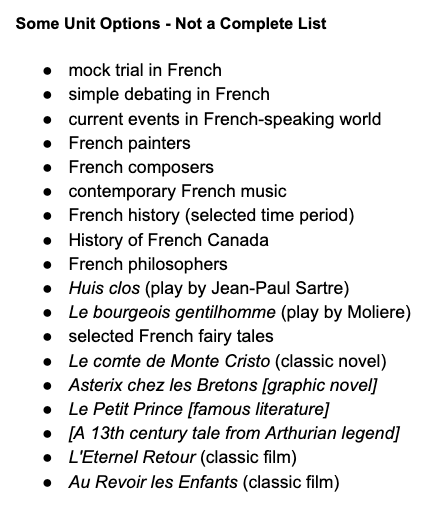

Everyone includes culture studies in their world language classes, especially at the higher levels when the language skills are enough to make many authentic culture forms accessible. May I propose to make this culture study the centerpiece of year three and four studies and that it is indeed possible to do this at level three with the right scaffolding techniques. The main reason to do this is that learning culture will stay with students longer and enhance their overall education more profoundly than learning a language they will most assuredly mostly forget.

The correlation between the quarter marks’ average [in a culture course] and the French Regents Examination [a measurement of communicative proficiency] average score was 0.70.

In the early 1990s, I renamed my French III course “French Civilization”. I made culture studies, with thematic topics determined by students, the centerpiece of the lessons.

Can you really teach content and still get kids ready for the Regents?

Let’s look at the data. I taught French from 1991 to 2004, then a few courses from time to time, and finally again in 2022-2023. I saved my final grade sheets since 1993. I wish to demonstrate that teaching culture using the target language is an effective means of getting students to communicative proficiency. I think the data backs up my claim. I have analyzed my students’ grades in French Civilization (what I had entitled my third-year course) from the 1994-1995 school year through the 1999-2000 school year. During that six-year period, I taught 86 students third-year French as a civilization course.

The data support this method.

The class average on the Regents during that six-year period was 80. The average of the quarter marking period grades for those students during that time was 82. The correlation between the quarter marks’ average and the French Regents Examination score was 0.70. The spreadsheet is available below. This strong correlation supports the idea that you can teach culture and build language proficiency. I submit that this method is better because of its long-term benefits to students in teaching them content much as they would learn in a social studies course. This is a life-enriching educational practice that still meets the communicative goals measured by world language examinations such as the Regents examinations in New York State.

How do you teach language and content?

Scaffolding lessons designed to make authentic culture materials accessible to students are in the wheelhouse of every language teacher. A complete training program is beyond the scope of this article. But a few worth mentioning are these: easier versions of classic texts, pre-teaching key vocabulary, training programs to help students construct meaning in a sea of unknown words, and surely coaching in the native language as students tackle the tasks. A culture course where the class chooses its topics of study will enjoy some motivation from interest alone. Good scaffolding lessons let teachers bring resources to accessibility and help students build confidence.

Student interest becomes a driving force.

Most students who advance to this level of world language learning are interested and usually are academic-minded. The freedom afforded to choose their learning seems ideal in a way Rousseau would appreciate. They’ll need to be brave to tackle plays written in the target language or try to understand a classic film. But my experience has been that interest and choice are really strong motivators.

Students who have complained that they don’t really end up very fluent from high school world language courses have found little comfort in the rationale provided by adults around them. It’ll get you out of college courses. It’ll make your transcript look good. It’ll help you order a meal at that French restaurant in town. Your English gets better. You’ll learn about other cultures. You’ll learn grammar. And the list goes on… But emperor has no clothes, and the band keeps marching him through town.

For third and fourth-year students in high school language classes, the data support the idea that culture classes lead to the level of communicative proficiency measured by standardized tests like the New York State Regents examinations. The level of proficiency students can actually achieve is fairly limited and maybe we should be more up front with students about that; set more reasonable expectations. Culture and civilization classes enrich a person’s education, a person’s life, in ways that just teaching them to ask when is the next train to Madrid won’t do.