Innovation has always developed in response to authentic, practical instructional needs of students and teachers. In retirement, I am enjoying teaching part-time remotely and this continues to inspire new apps and coding enhancement.

You know, Reader, if you take a good look at what you are using to teach in digital spaces, you may observe like I did that a lot of it is software originally designed for office workers. Word processors, spreadsheets, presentation software and the like: these were made for adults doing largely self-directed work in office work. We are so accustomed to these apps that we hardly realize that they don’t ever quite exactly fit for us in the classroom; that we are always creating modifications and work-arounds to make them work. And we get by…

21st century learning spaces, a paradigm often expounded here at this site, are virtual workspaces that really “fit” secondary instruction in ways that office productivity products do not. Let’s address monitoring student work.

One of my classes this year is an AP French class down in Texas. My objective was to teach them a new grammar point. During our in-class practice, I needed to be able to monitor their work while they were doing it.

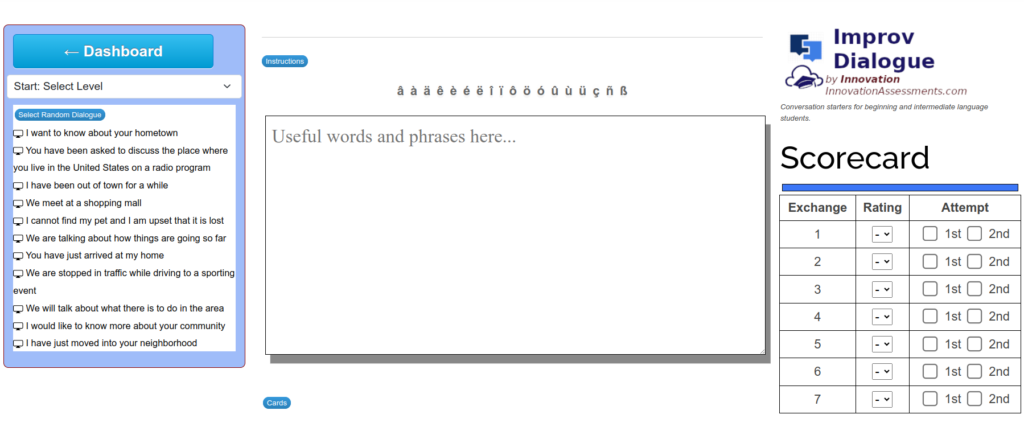

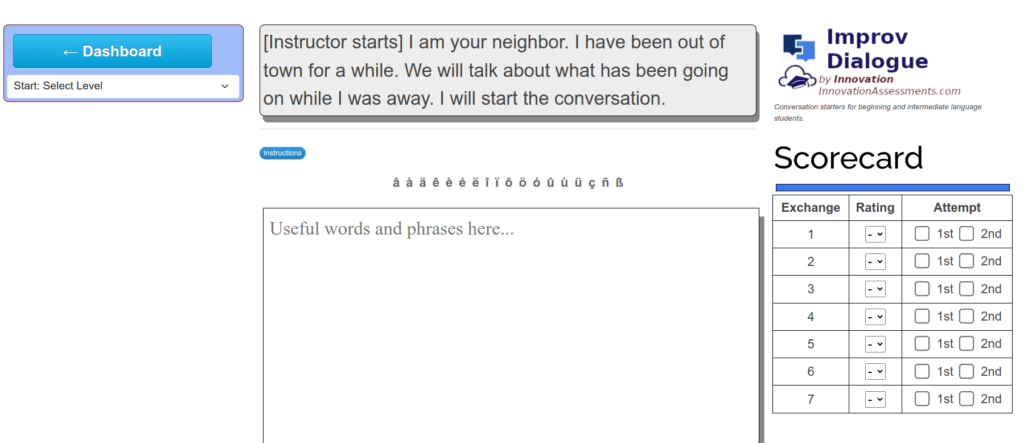

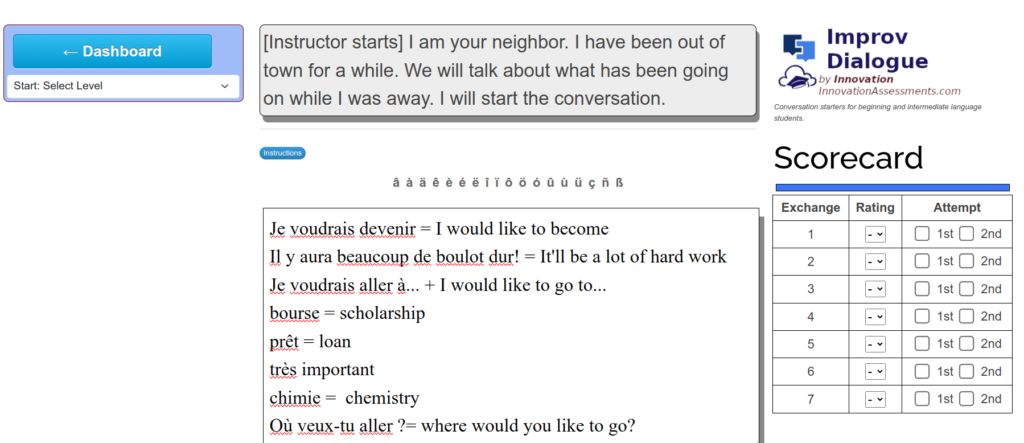

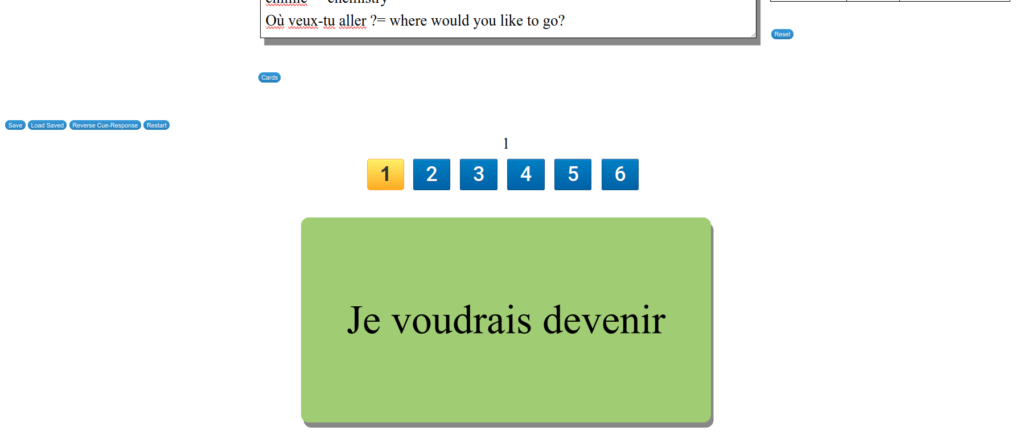

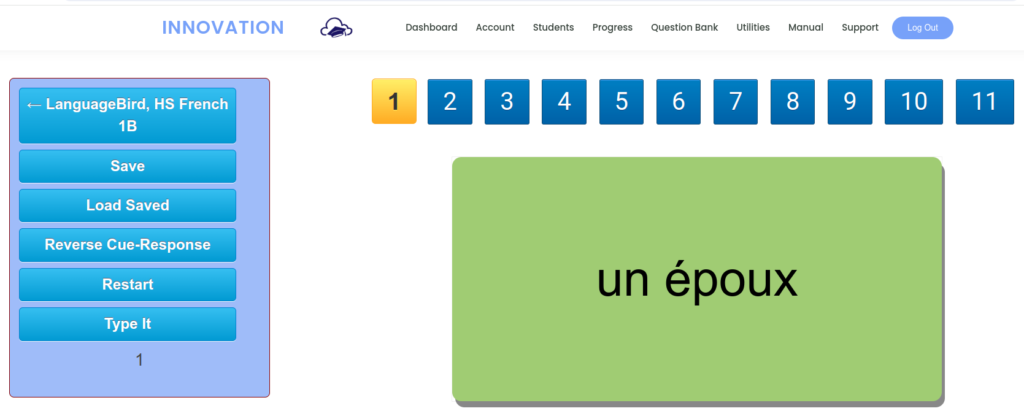

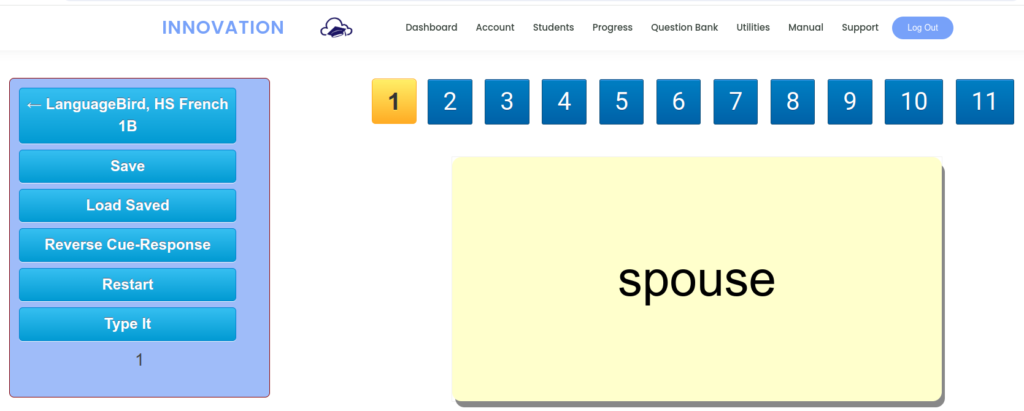

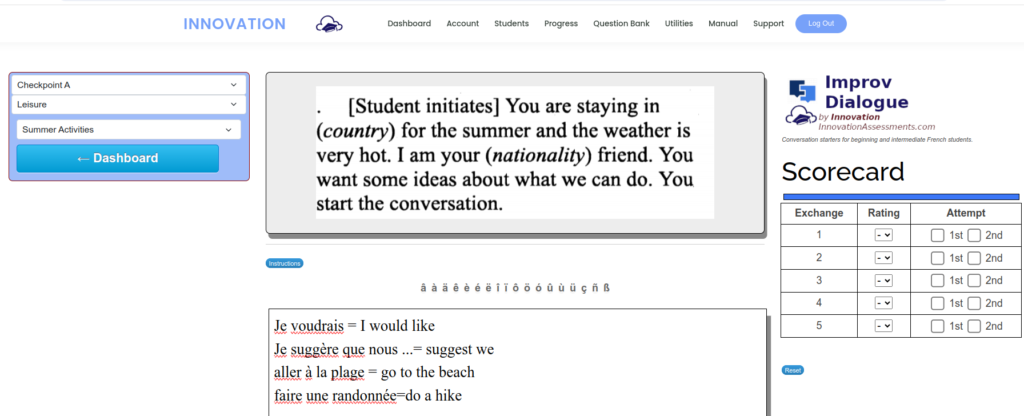

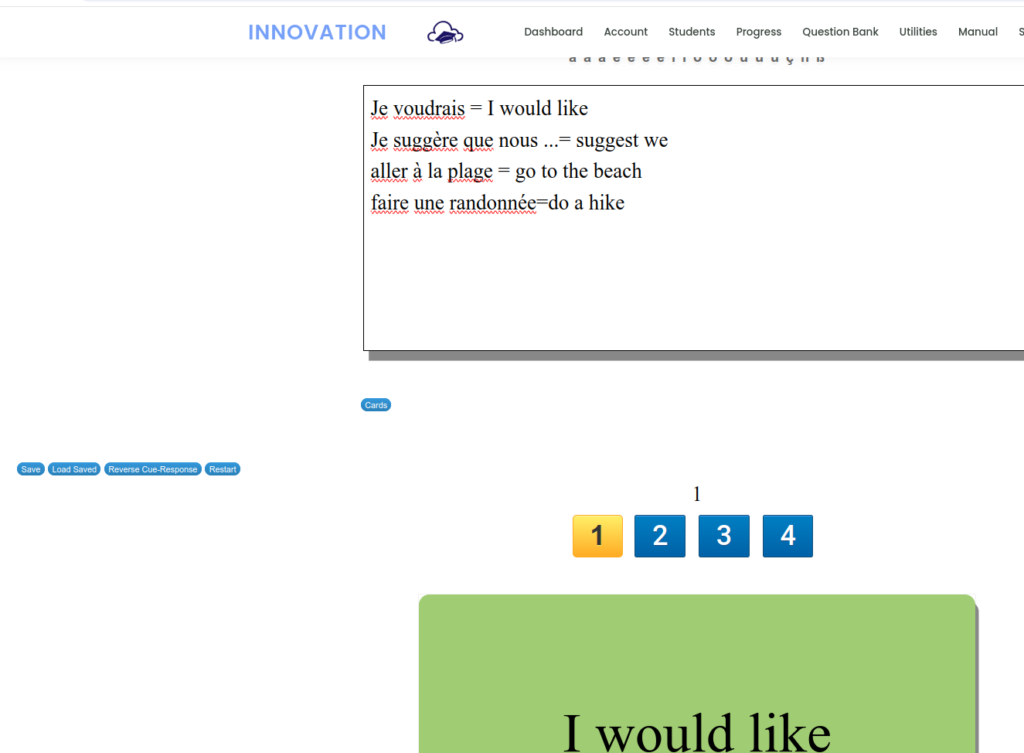

Reader, you may already be familiar with Innovation’s grammar learning app. Students learning world languages benefit from practice transforming and generating utterances from prompts. The app meets this need by providing a digital learning space that is interactive. An algorithmic AI lets students know how close they are to the answer, for example, and the instructor can transform the content into a “live session” in which students participate in real time much like the famous Kahoot! game.

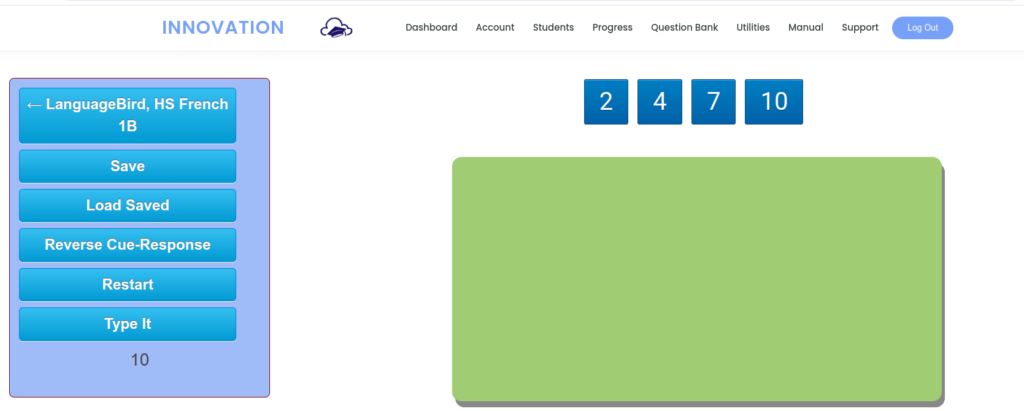

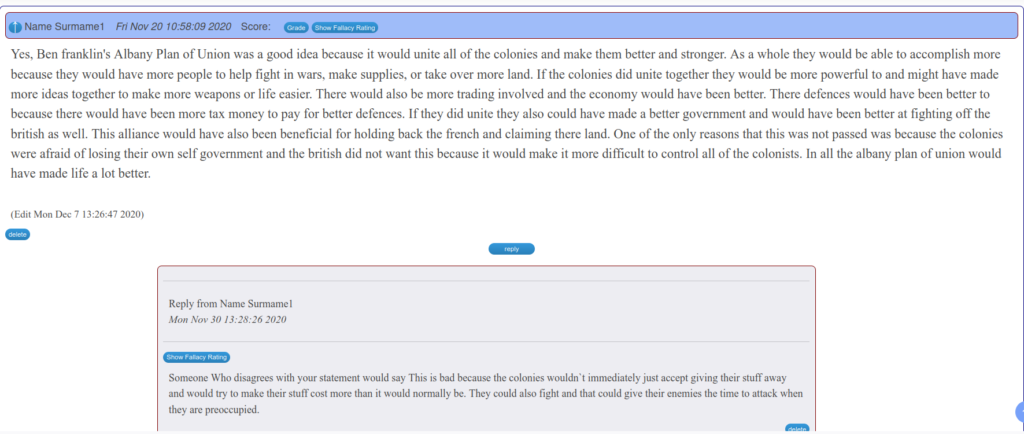

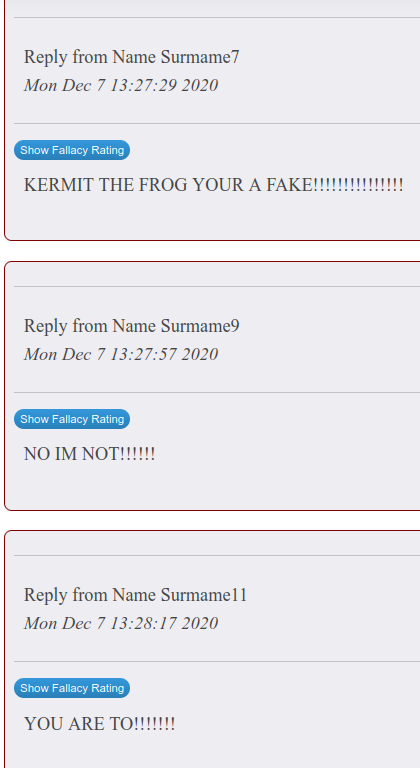

Adolescents can sometimes be distractible. In an in-person classroom, I have reasonable observational capacity to notice and redirect distracted students. In remote teaching, this requires some additional effort. What if I could see the student’s’ progress in real time as they worked?

People learning new things can sometimes make mistakes. In an in-person classroom, I can wander the room and peer over students’ shoulders. I can try to catch mistakes as they make them and offer correction in a more immediate way. It’s a shame to have to wait a day or two before addressing writing errors. Immediate feedback is more effective so that the other practice examples go well and inculcate the correct syntax. What if I could peer over everybody’s virtual shoulders while they practiced their new writing skill?

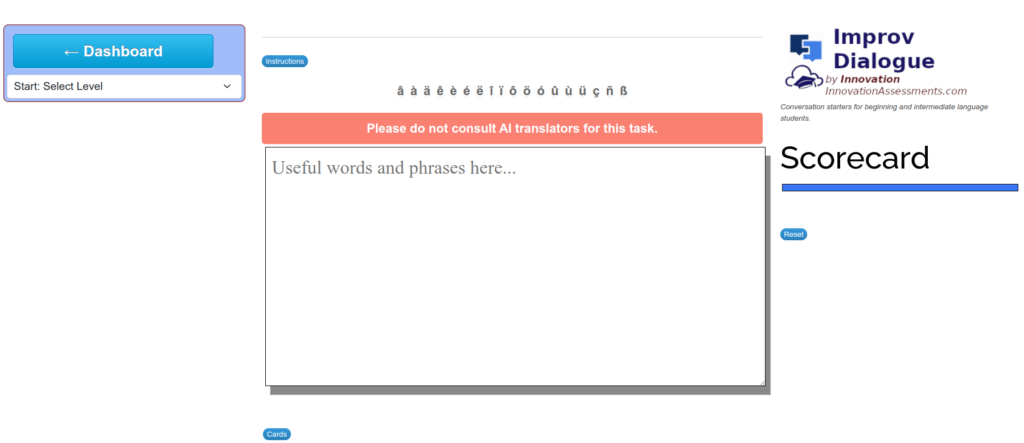

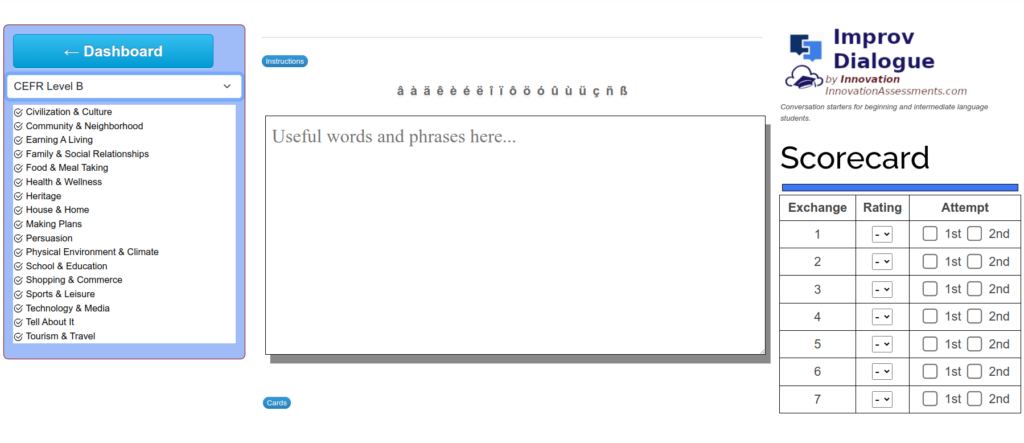

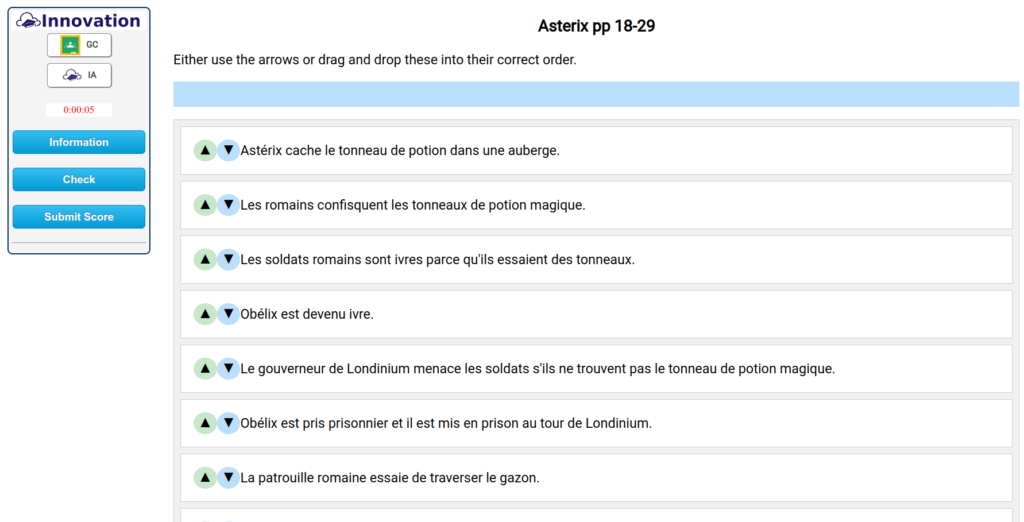

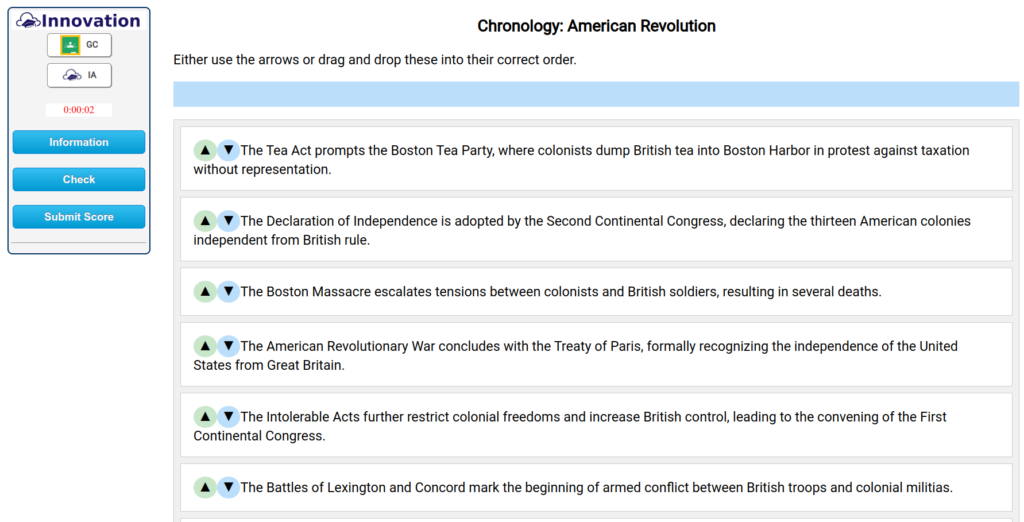

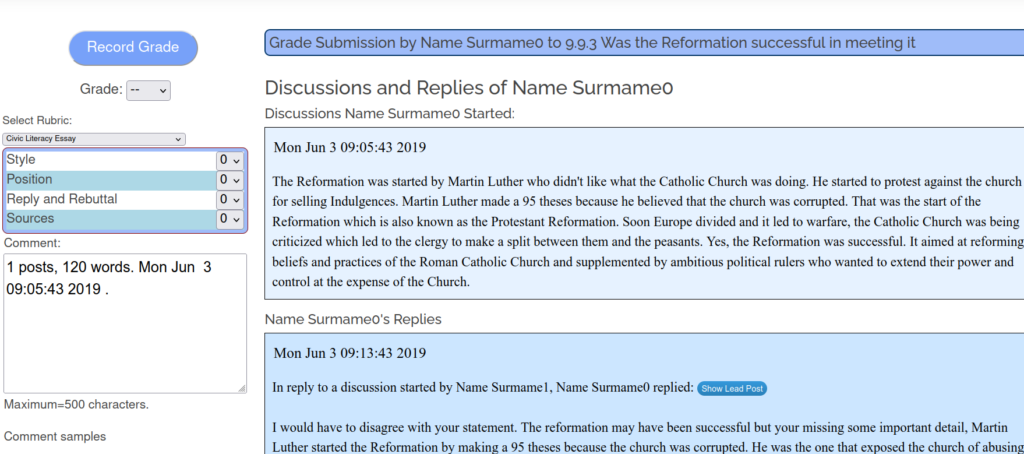

The monitor app is now installed at Innovation’s short answer and world language composition tasks. It allows the instructor to view all of the students currently with any saved work on the task. Click the student name, and the instructor can see their work in real time (well, there’s a ten second lag for technical reasons). This work is refreshed every ten seconds. In the short answer monitor, the number after each name tells how many responses they have saved.

In situations where the teacher may wish to share the screen with the class, they can hide the student names and, for the short answer tasks, hide the correct answers.

The way I like to use this is as follows: I use two monitors. Monitor 2 is shared with students. I can set the names to “Anonymous” and share the monitor. I select students at random from time to time to check their progress. I may focus on someone who is behind. I may focus on someone I know needs more support (I can see the names before setting anonymous). In monitor 1, on the Zoom or Teams call, I can use the chat to message students corrections, suggestions, redirections if they appear off task, and so forth.

To activate the monitor, scroll to the activity in your dashboard course playlist. You’ll find “Monitor Class” in the task dropdown. Monitor is installed for short answer and composition tasks at present. While you are wandering around the site, why not visit our newly opening shops? You can purchase my own activities, PowerPoints, and DBQs for social studies.