Can Vocabulary Knowledge Predict Content Knowledge? Unveiling Insights from Classroom Practice

Encountering a scholarly paper delving into curriculum-based measures (CBM) for content area secondary courses like social studies ignited my curiosity. Eager to implement and extend their research, I embarked on a journey within my own classroom. As an educator committed to maximizing my students’ potential, I aimed to investigate whether vocabulary knowledge could serve as a predictor of content comprehension. Through practical application and careful observation, I sought to unearth valuable insights to refine my teaching methodologies. Here’s what unfolded during this intriguing exploration.

The intersection of vocabulary and content knowledge has long been a subject of interest in education. While vocabulary is recognized as a fundamental component of academic proficiency, its role in anticipating students’ understanding of intricate subject matter remains a matter of debate. The paper I encountered proposed that assessing students’ vocabulary knowledge through CBM could offer valuable insights into their grasp of content area material, particularly in disciplines like social studies characterized by specialized terminology and concepts.

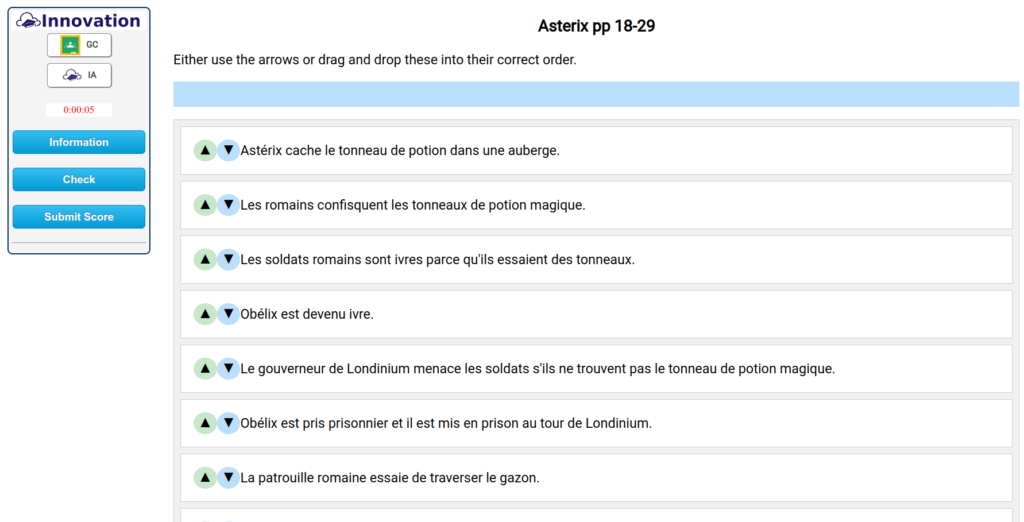

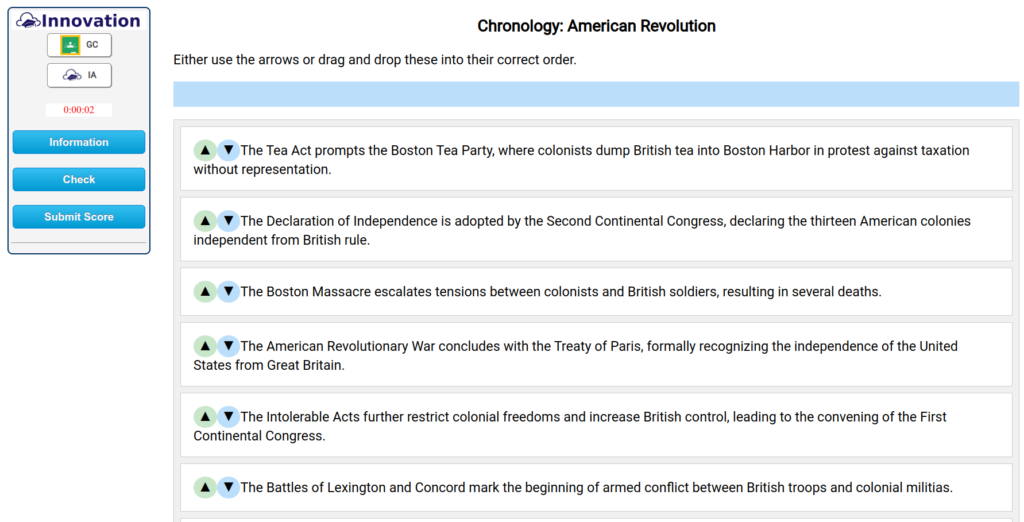

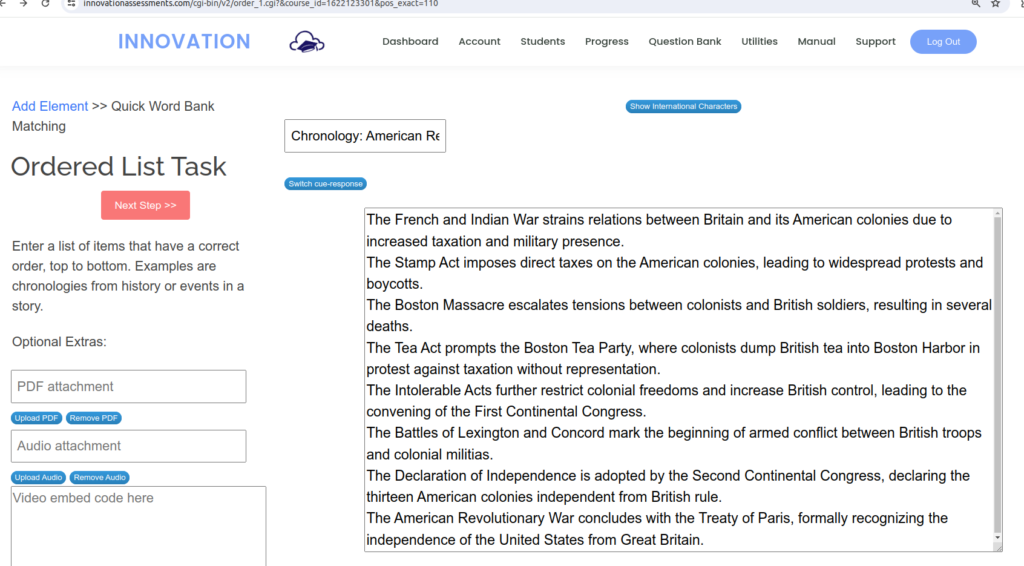

To test this hypothesis, I integrated vocabulary-focused CBM into my social studies curriculum, meticulously tracking students’ progress across multiple units. I developed targeted vocabulary assessments, quizzes, and assignments tailored to evaluate students’ familiarity with key terms and concepts relevant to each unit of study. Additionally, I incorporated vocabulary-building exercises into classroom activities, discussions, and readings to reinforce students’ comprehension and retention of subject-specific terminology.

Through continuous assessment and analysis, intriguing patterns began to emerge in students’ performance. Those exhibiting proficiency in vocabulary consistently demonstrated a deeper comprehension of the content material. They showcased their understanding by articulating complex ideas, drawing connections between different topics, and applying their knowledge in diverse contexts. Conversely, students grappling with vocabulary challenges often struggled to grasp the underlying concepts and themes presented in the curriculum.

One significant revelation was the predictive capacity of certain high-utility terms in gauging students’ overall content mastery. Terms acting as linchpins or conceptual anchors within the curriculum correlated strongly with students’ performance on unit assessments and projects. By prioritizing the teaching and reinforcement of these critical vocabulary terms, I could scaffold students’ learning and facilitate deeper engagement with the subject matter.

Moreover, I observed that vocabulary instruction served as a gateway to content proficiency, enabling students to access and comprehend complex texts, primary sources, and multimedia resources more effectively. Equipping students with the linguistic tools to decode and interpret content area material empowered them to become more independent and self-directed learners.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations of relying solely on vocabulary knowledge as a predictor of content understanding. While vocabulary forms a foundational aspect of academic literacy, it should be viewed as part of a broader assessment framework. Factors such as background knowledge, cognitive skills, and socio-cultural influences also significantly influence students’ learning experiences and outcomes.

In conclusion, my exploration into the relationship between vocabulary knowledge, CBM, and content understanding provided valuable insights into student learning dynamics within the social studies classroom. While vocabulary instruction can undoubtedly enhance students’ comprehension and retention of subject matter, it should complement a comprehensive approach to teaching and learning. By integrating targeted vocabulary CBM with engaging content-based activities and assessments, educators can create enriching learning experiences that foster deep understanding and critical thinking skills in students.