Though retired, I still teach a few courses a day remotely. This week, I attended a professional development meeting for one of the companies for whom I teach, where a presenter used a popular interactive presenting app. The presentation itself was excellent. The app, however, was another matter entirely.

I will grant that, as a developer of educational technology myself, I am a harsh critic. But I suspect even the hundred and fifty or so others on that Zoom call would agree. The app was heavily gamified, filled with sound effects and floating reaction emojis designed to promote “engagement.” Each emoji triggered a popping bubble sound as it drifted across the screen. Participants continued clicking them even after being asked to stop, while the presenter was attempting to explain how to construct a complex AI prompt. The result was not engagement, but distraction.

My earlier posts have noted my long-standing skepticism of gamification. Its promoters often cling to the old trope that if students are having fun, they will not even realize they are learning. Forgive me for sounding like the old fogey that I am, but that idea has always struck me as pedagogically misguided. I want students to know they are learning. More importantly, I want them to learn how to guide and regulate their own learning. Attention should be directed toward the material, not toward points, sounds, or game mechanics.

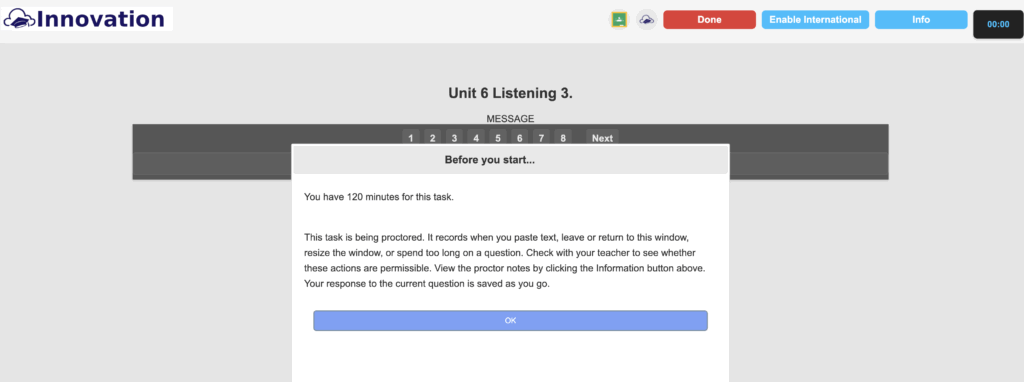

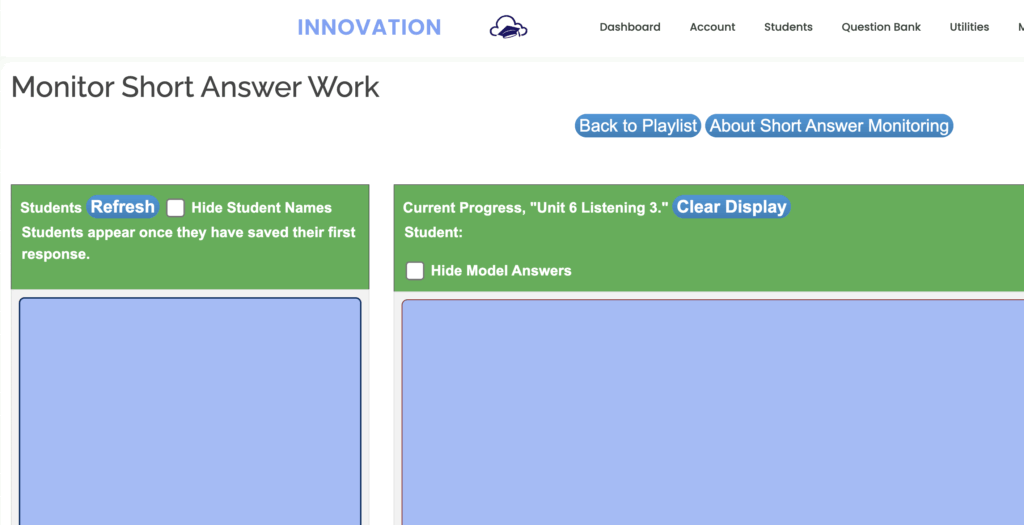

If you explore the Innovation platform, you will notice that it is intentionally plain. Interactive tools include emoji responses, but they are subtle, silent, and easily disabled. This is by design. The platform reflects how I actually teach, rather than how a game designer imagines learning should feel.

Because most teachers are not developers, we often adapt software that was never designed for classrooms in the first place. We rely on office productivity tools or on educational software built by developer teams whose instincts lean more toward gaming than pedagogy. I occupy an unusual position as both teacher and developer, and I find great satisfaction in coding applications that behave the way a teacher actually needs them to behave.

The Classroom is Not the Office

Having taught since 1991, I have lived through the entire technological transformation of education. My first classroom had chalkboards and binders. My last, before retiring three years ago, had 1:1 student laptops and a SmartBoard. One persistent problem has been that much of our classroom software originated outside education, particularly in office environments.

When we placed laptops running word processors and spreadsheets in front of students, we gained powerful tools but lost a degree of visibility and supervision. In 1991, it was nearly impossible for a student to hide off-task behavior behind a notebook. In 2026, it may be a hidden browser tab. What was marketed as “real-world experience” often came at the cost of instructional control.

At Innovation, I aim to design learning spaces that originate in education rather than being imported from the office or the gaming world. Our writing tools include optional AI proctoring and live monitoring so instructors can observe student work in progress. Our assessment tools provide similar oversight, along with messaging features that allow teachers to guide, redirect, or support students in real time.

In short, the goal is not to make learning noisier or more entertaining. It is to make it more focused, more observable, and more teachable.

Good educational technology should not compete with the lesson for attention. It should support the teacher, clarify the task, and fade quietly into the background of learning.

After more than three decades in the classroom, I have come to believe that the best tools are not the loudest or the most entertaining, but the ones that respect how learning actually happens: through focus, guidance, and sustained attention. If our software cannot preserve those conditions, then no amount of animation, gamification, or sound effects will make up for what is lost.